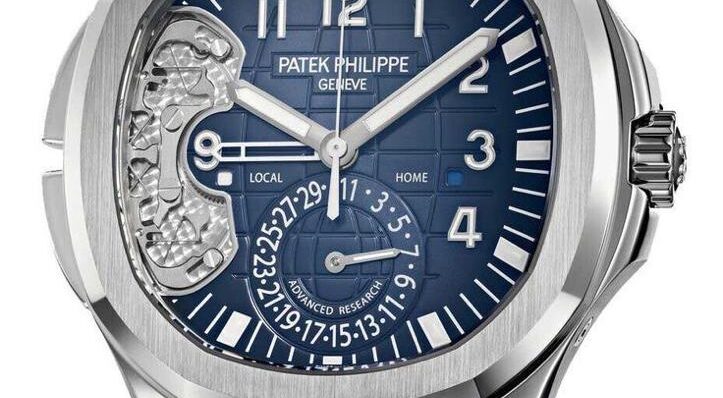

The Patek Philippe Aquanaut Travel Time Ref. 5650G Advanced Research

One of the most interesting technical presentations this year came from Patek Philippe, whose Advanced Research Program announced two new innovations. This is the sort of thing that, unfairly or not, tends to take a back seat to more quickly graspable hot news. However, it’s something worth paying attention to. The two innovations announced aren’t necessarily super sexy at first glance, but they offer, on the one hand, a new system for activating a complication that uses no conventional pivots; and as well, a new method of forming a balance spring that allows Patek to offer shockingly good rate stability: just -1/+2 per day, in general production watches. That’s news.

The Patek Advanced Research Program

The Patek Advanced Research Program is part of a much larger story, which is the development of silicon components for use in watchmaking. Much of the original research into silicon components took place at the Centre Suisse d’Electronique et Microtechnique (CSEM) and was underwritten by a consortium that included Rolex, Patek Philippe, and the Swatch Group (all of which have in subsequent years adopted the technology for production watches). The Advanced Research Program at Patek Philippe is essentially an outgrowth of its participation in the CSEM group, and the very first practical expression of that program was announced in 2005, when the first Patek silicon component – an escape wheel in a proprietary silicon dioxide formulation known as Silinvar – was announced, along with a Silinvar escape wheel. These components are cut from silicon wafers with a fabrication process known as DRIE (Deep Reactive Ion Etching).

The advantages of silicon are well known – its surface hardness (twice that of steel) and smoothness means it’s possible to manufacture interacting mechanical watch components that don’t require oils, and which can be fabricated with extreme precision as well. This was also the year that Patek released its first Advanced Research Project watch: the ref. 5250 Annual Calendar, in which the Silinvar escape wheel was first used.

Though silicon is sensitive to temperature changes, it’s possible to produce formulations that don’t have that property; Silinvar is one such formulation. The word has some deep roots in watchmaking, by the way; it’s related to the name Invar, which is the term for a special nickel-iron alloy with a very low tendency to expand when heated. (“Invar” is from “invariable,” as in, invariable dimensions regardless of temperature.) It was invented in 1896 by Charles Guillaume, who would win the Nobel Prize for it in 1920; Invar went on to be widely used in scientific instruments and in watch and clockmaking (high precision pendulum regulators often had Invar pendulums).

However, probably the the single biggest news in the entire story arc was the introduction of the Spiromax balance spring the next year. Made of Silinvar, the Spiromax balance spring was formed in such a way as to give the advantages of a conventional Breguet or Phillips overcoil balance spring – basically, better isochronism than that obtainable from a flat spring – but with less height; all other things being equal, a Spiromax balance is one third the height of an overcoil balance spring. Spiromax springs are unaffected by magnetism, and with a mass much lower than Nivarox, less affected by external shocks, or gravity. The Spiromax balance spring was first released in a limited edition of 300 pieces in the ref. 5350 Annual Calendar but it’s now widely used by Patek Philippe, in virtually all its watches other than high complications.